Pathogenesis, by Jonathan Kennedy (London, 2023).

I have often found it curious that in the years since completing my PhD, my historical interests have veered away from the topic I studied for so long and towards completely different areas – though actually this may be more standard than not. One of the interests I developed is in diseases and their impact on human history. This began a number of years back when I picked up a book on a history of disease, namely Kinsey Dart’s Yesterday’s Plague, Tomorrow’s Pandemic? A history of disease throughout the ages, in which the author argues that the infamous Black Death, the plague that struck Europe in the 14th century, was not bubonic plague. This astounded, baffled and annoyed me, because while the argument was strong, at no point did he propose an alternative hypothesis. And of course, as science has now shown, he was in fact incorrect – numerous pieces of evidence now exist proving that 14th-century plague was in fact caused by Yersinia pestis. But the discussion got me hooked, particularly when I discovered that bubonic plague still exists in the modern world and, in fact, in the United States – though mostly west of the Mississippi.

This book by Jonathan Kennedy was a going on holiday gift from my other half, and I positively devoured it. Kennedy writes in an academic fashion, describing things in scientific terms as well as historical, yet makes them accessible to those without a Biology degree. The frontispiece is a map of the spread of various diseases throughout history, from Neolithic Plague to Covid-19 – there is nothing I love more than a good map! (take a look at the end of this post)

The introduction is subtitled ‘Primordial plagues’, utilizing a word that for me stirs up memories of things X-Files and of course Darwinian. Perhaps most appealing to me is Kennedy’s writing style, a mix of intellectual and tongue-in-cheek, providing facts in an intriguing fashion. One of the first that struck me was the description, on page 10, of how species’ adaption to retroviruses led to the evolution of gestational pregnancy rather than the laying of eggs.

To give you a feel for his style:

“Freud’s suggestion that psychoanalysis is more sigificant than the Copernican or Darwinian revolutuions seems a little, well, egotistic.”

Pathogenesis, p.2.

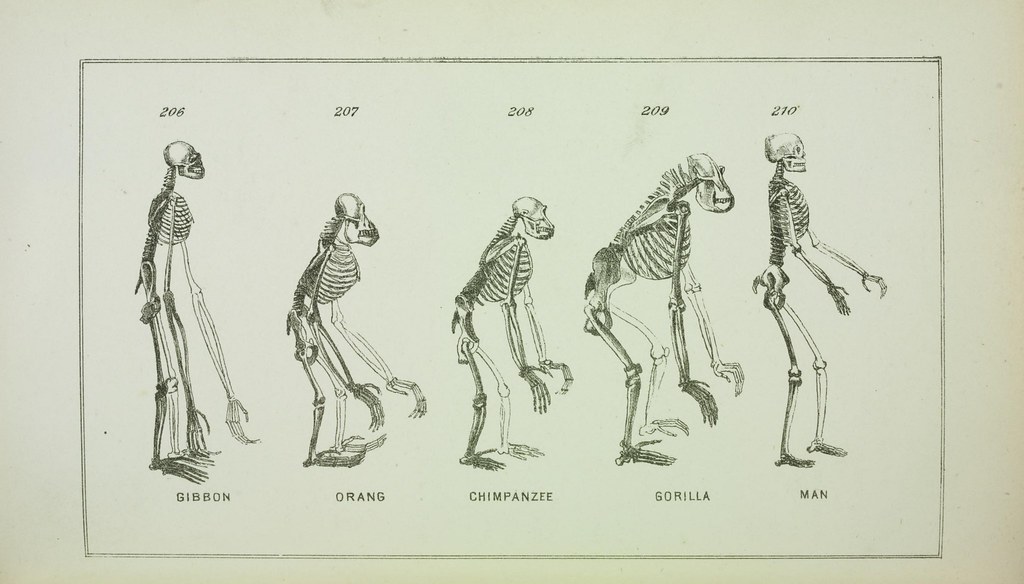

As the book moves through time, Kennedy does an excellent job of outlining the more traditional views, and then either upending or updating them with the data gathered more recently as our biological technology improves. He shows how history is anything but static or stagnant – rather it is constantly changing as we learn more. A key example of this is his discussion of the pre-eminence of Homo sapiens and slow disappearance of other human species such as Homo neanderthalensis and the more regionally-specific species Homo florensiensis and Homo luzonensis. It was not, as I was taught in grade school, a single line of evolution but instead a branched tree that overlaps and commingles – we know many modern humans carry Neanderthal DNA, for example – and just because a group of people migrated into an area at a particular time does not mean they stayed there.

As a student of the bubonic plague, I devoured a section on the ‘Neolithic Black Death’, during which Kennedy describes evidence of the Yersinia pestis bacterium in the traces of skeletons from Sweden, around 5,000 years old.

The key difference, Kennedy, explains, between this ancient plague and the one that devastated 14th-century Europe, was that it was non flea-borne until early in the first millennium BCE. The implications of this change are evidence in the study of both the Justinian plague and the Black Death.

“By comparing the genomes of these different strains of bacteria it’s possible to calculate how long ago they diverged…[from] a common ancestor that was circulating about 5,700 years ago.”

Pathogenesis, p. 67.

Moving onward, Kennedy spends a healthy amount of time discussing the diseases that wreaked havoc during the Columbian era, but also in flipping the coin to examine the impact of tropical diseases on colonial Europeans. For those of us living in Scotland, there is a key case study of how a disastrous seventeenth-century attempt to settle in Central America caused financial disaster and, not indirectly, to the union of the crowns of England and Scotland in 1707, with political ramifications still felt today.

While one might read some of these sections as more focussed upon the European settlers than the destruction of the native population, the purpose is not, I feel, to devalue that genocide, but instead to demonstrate how Mother Nature fought back, in some cases quite effectively. Kennedy also addresses how the resilience of the native Africans kidnapped and brought to the Americas was to some extent their downfall – they were more prepared for the illnesses of the tropical region yet also had immunity to Old World diseases like smallpox, and so were heartier than both Europeans and the native population of the Americas. This heartiness led to inconceivable suffering.

As Kennedy moves into the 20th century, he begins to look at the influence of politics on disease prevention and vaccination. He also spends a great deal of time examining the links between poverty and disease.

“One link between deprivation and non-communicable disease is unhealthy eating. A recent study found that the poorest 10 per cent of households in the UK would have to spend over 70 per cent of their income in order to follow healthy eating guidelines. As a result, we see higher levels of obesity in low-income areas.”

Pathogenesis, p. 280.

For those of us living in modern Britain, it is chilling to read about the impact of post-Thatcher cuts to the NHS on modern life and health. Kennedy cites a British Medical Journal study estimating that more than 10,000 extra deaths each year may have been caused by cuts in UK government spending on health (Pathogenesis, p. 282.).

This kind of observation, combined with his earlier discussions of the evolution of man and its relationship with disease, make this book absolutely fascinating and a must-read for anyone interested in the development of the human race over thousands of years.

My only criticism lies in the perhaps inevitable tendency that Kennedy, like many other academics, has in arguing that his study is the most significant in history – that the world changed because of these little-considered forces, more sigificant than any other. One of my favourite moments of study as an undergraduate was during my Fall of the Roman Empire class when we were all asked to write a paper on why we felt the empire collapsed – and every one was different. One hypothesis was to blame women (not in a misogynist fashion so much as political), another Christians, another, beards. We all did well, we all had good arguments, and in a way, we were all right.

Which makes clear that there is never one answer as to why anything happened in history, never only one catalyst – you can easily argue that your hypothesis is correct, but really there is always a multitude of factors in any historical shift. Nonetheless, Kennedy’s argument that disease is often missed, is a good one. It is also one that has, until recently, been very hard to research, as much of the evidence we would like to have is gone. In many cases, the eyewitnesses of a disease or epidemic did not have the language to describe symptoms scientifically. There will always be a debate, for instance, as to whether certain deaths in the 16th century were caused by leprosy or syphilis, as without biological evidence, the two look incredibly similar. This, then, is where this book can be seen as the start of an exciting new period of historical research and knowledge – as our scientific methods reach new depths of inquiry, new evidence will be found and examined to help answer questions. In many cases it may even change the course of what we thought we knew. And that, in my humble opinion, is what the study of history is all about.

Map of the spread of pathogens throughout history, from Pathogenesis.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Pathogenesis-infectious-diseases-shaped-history/dp/1911709054