I must start off this post by prefacing that this is my favourite classic Disney movie and was watched by my me and my best friend at least once a month when we were young. We frequently dressed up as our favourite characters and fought over who got to be the ‘best’ fairy. And who was the best fairy. And whether the dress was better in blue or pink.

As we have grown up, it remains a familiar touchpoint for both of us, and she will often pick up something Aurora-related to remind me of the film that dominated our childhood (alongside Clue and The Princess Bride). My Aurora-dress Christmas ornament is one of my favourites and most-treasured.

The movie holds more than childhood memories, though – it was one of my first exposures to the medieval world to which I have devoted so much of my life. While I can’t say that our obsession with Sleeping Beauty led directly to my studies, the art and medieval aesthetic are striking.

Background – the story of Sleeping Beauty

Before I get too far into analysis of the movie, I wanted to take a quick look at the story behind the fairy tale. Disney, as it often did, softened the story quite a bit from its inception, in a French chivalric romance from the mid-14th century (Disney held on to this idea, locating the film in France and with the characters mentioning the century). Early versions of the story are considerably less romantic and certainly involve issues of consent – the first story involves the essential rape of the princess while she sleeps and the birth of a child. There was also a second half of the tale that involved the troubles of the princess and her husband after their marriage, which may have been the basis for other tales.

Fairies were added in the 17th century, and the intercourse softened to a kiss. This is roughly where the Brothers Grimm stepped in and separated the story of Briar Rose from later tales – Aurora was a name picked up by Tchaikovsky when he wrote his ballet.

With fairies came the further idea of good and evil fairies – the basis of the Maleficent character – who alternately gift and curse the princess. In some tales, there is a hint of a former relationship between Maleficent and the king – such as is later suggested in the 2014 Angelina Jolie movie of the same name – though this is not widely acknowledged. What does seem relatively static throughout the versions is the princess’s relative lack of agency, something that has aroused numerous criticisms of the story and the movie. But I will come back to this.

Alongside the film, I was also familiar as a child with a version of Sleeping Beauty re-told and beautifully-illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman. Each page is meticulously detailed and stunningly drawn, and the story itself sticks with an older version of the tale, where the princess does sleep for 100 years, and the travelling prince hears about her through legend. It is a much more haunting idea than the Disney version, and also provides a touch more incentive for the evil fairy’s actions.

The movie

Small disclaimer: I was lucky enough to find some screen caps of the film online, and so all of the artwork below belongs not to me but to Disney.

Disney clearly looked at several versions of the tale and decided, in the almost decade of development time, to stick with some of the most common themes: a childless queen who has a miracle baby, an evil fairy offended by not being included in the celebrations, good fairies who temper her curse from death to long sleep, and a sleep only ended by true love’s kiss. Disney reduced the number of fairies to three – from seven, twelve or thirteen – and made the quite reasonable choice to have the true love actually meet the princess before she falls asleep. The length of sleep was also shortened considerably to only a few hours and not the 100 years of legend.

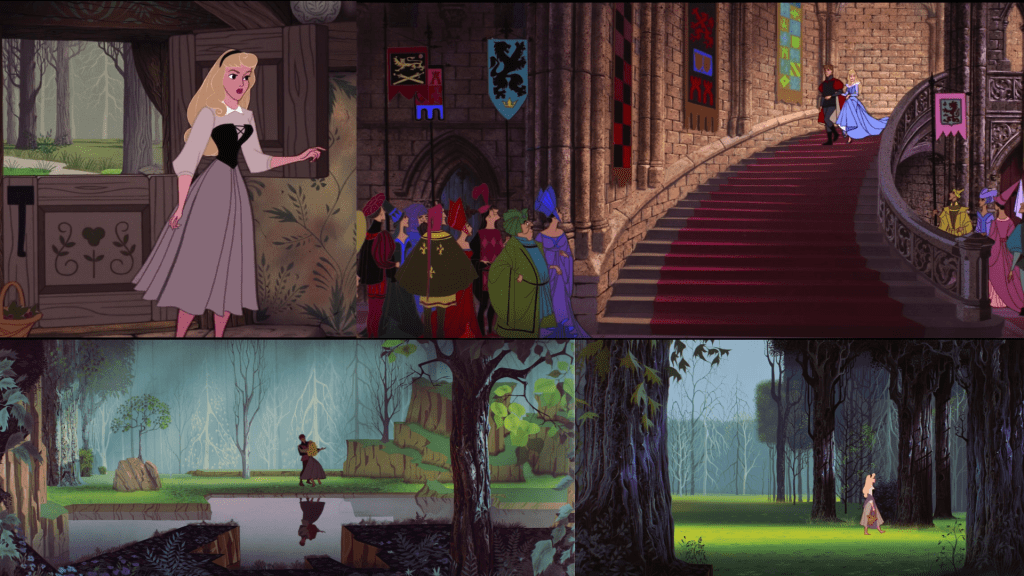

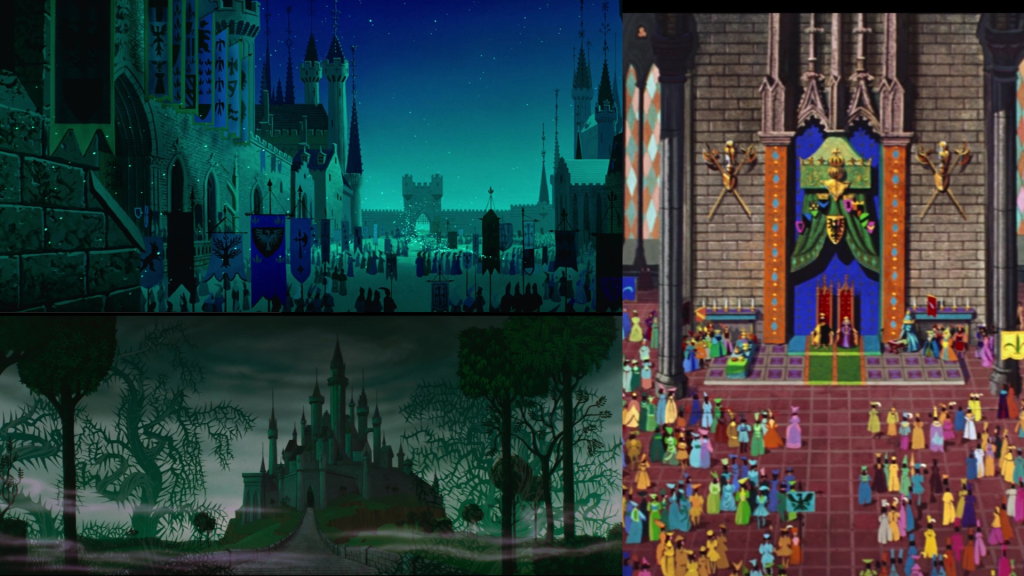

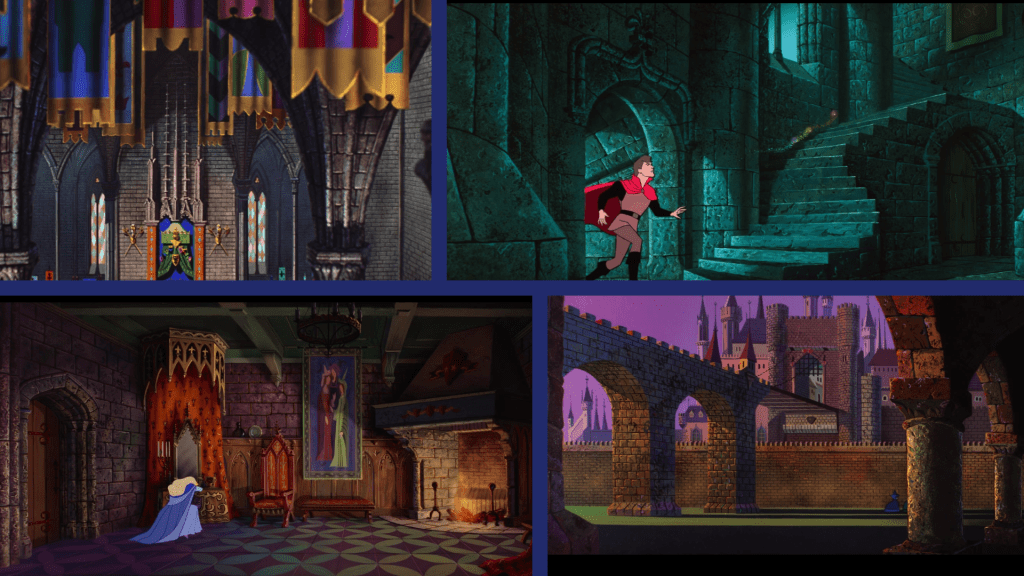

Disney made a few other very interesting choices when producing this movie. Firstly, one man was put in charge of the entire background design and visual feel of the film. This may be why it is so different from other animations of the time, and why I was so drawn to it – the background images behind the animation are simply stunning, with intricate details. The forests are alive and trees uniquely shaped; the castles are gothic and covered in carvings and textured stone; there are banners and flags with coats of arms and all sorts of medieval feudal emblems – fleur de lis, crowns, dragons, eagles. Even the woodcutter’s cottage in the woods is beautifully decorated in patterns we would not really see again until Frozen.

Secondly, the music is so unusual for a Disney film that even my other half, who deigned only to watch the last 20 minutes with me, remarked on how surprising it was. The reason is of course that the composer adapted most of the score from the Tchaikovsky ballet, infusing the story with a richness and depth of emotion. Even the main love song ‘Once Upon a Dream’ is written to the tune of Tchaikovsky’s Garland waltz. It is clear that the animators worked hard to match the images to the music; the three fairies arrive in a beam of light to flutes, and during the final battle the clash of cymbals matches the crashing lightening and eruption of the thorny thickets.

The beautiful artistry and music separate this movie from the other princess films made around this time such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarves or Cinderella (also a favourite if only for the mice). But, there is plenty of traditional Disney about it too – the characters are familiar, with the voice actors like Eleanor Audley, Verna Felton and Barbara Luddy recognisable from Cinderella, Lady and the Tramp, Alice in Wonderland and 101 Dalmatians.

There are anthropomorphic characters such as the friends Aurora meets in the woods and sings to – a common theme for Disney princesses who are often lonely and more likely to have animal companions than human ones – though they do not talk. Some of the artwork is also reminiscent of other Disney works, in particular Fantasia – the self-propelling mop and broom, the evil henchmen dancing around a green fire, and even the dragon which Maleficent becomes in the finale all look vaguely familiar.

One of the most regular criticisms of the Disney films of this era is that the main female character, usually the princess, is one of the least interesting in the film. She is the focal point about which the events rotate, but she has very little actual agency, and often very few lines. This can certainly be said of Aurora, who sings a lovely song but then spends half of the movie, well, asleep, and is famous as the eponymous Disney character with the fewest lines, second only to Dumbo. Furthermore, she is of that era of princess where it takes only an outfit change to make her a convincing Barbie – long slender legs, impossibly narrow waist, golden curling hair and large blue eyes. (I confess to always longing for hair that curled at the end like hers, though I wanted red not gold). Her beauty is mythic, magical, modelled after the equally breath-taking Audrey Hepburn.

What must be said about Sleeping Beauty though is that while the main character is not hugely compelling, there are plenty of strong female characters around her.

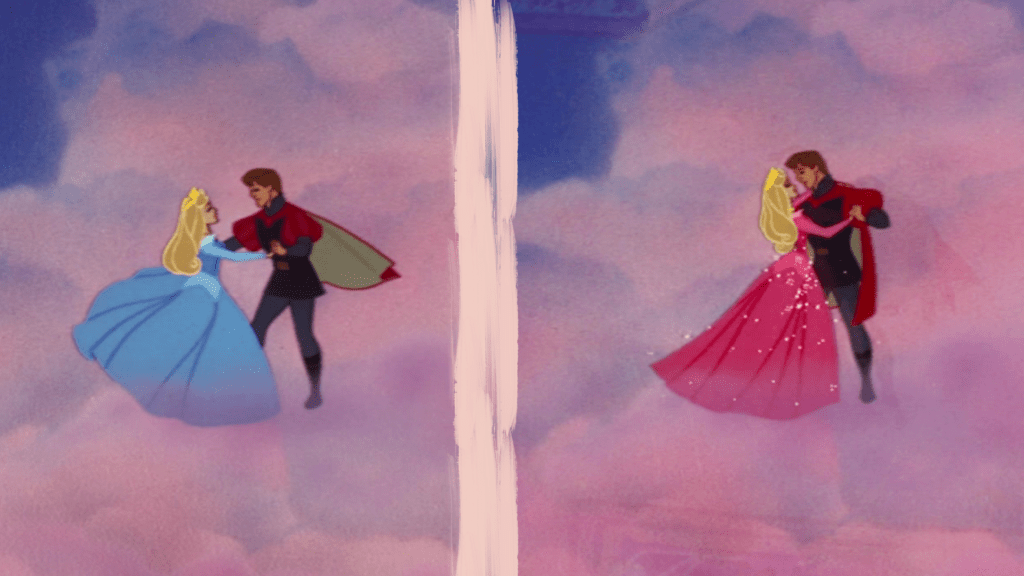

Firstly, the three fairies: Flora, Fauna and Merryweather. While they may be a touch daft at times, they are strong and powerful and take control of most of the movie’s main events; the red fairy (Flora) in particular is the leader while the blue fairy (Merryweather) is spunky and fun. At times one might argue that they cause more trouble than not (it was their childish fight over dress colour that alerted Maleficent’s raven to their hideout in the woods), yet they are instrumental to the defeat of evil.

Secondly and perhaps most importantly, there is the fantastic villain, Maleficent. Even before her reinvention in the 2014 film, she was a fascinating character who is at least partly misunderstood. She wasn’t invited to the princess’s christening, and if you go back to some of the original stories, it is because she was the black sheep of the royal family and may even have been Aurora’s aunt.

Whether part of the family or not, she was deliberately left out while younger, prettier fairies were invited. One might say that her revenge of cursing the princess with death was overkill, but then again, she is the villain. And she is captivating – strong, deliberate, graceful and not lacking in majesty. I believe that writing has been done on the tendency of early Disney films to make most of the villains older females as though there is nothing worse – Snow White, Cinderella, Little Mermaid, 101 Dalmatians, even to some extent Beauty and the Beast – but one cannot argue that they aren’t strong characters with agency of their own. Personally, I thought being Maleficent would be great fun as a child; there was something intriguing about her intelligence and her freedom, and her quick change from humour to rage. In fact, when we played Sleeping Beauty dress-up, my friend and I often chose to be Maleficent, or one of the fairies – never once did either of us dress as Aurora.

The main character is essentially a medieval Barbie, but there are strong female characters around her.

The three fairies brave the Forbidden Mountain to free Prince Philip, and in one of my favourite moments of the movie, an easily frustrated and feisty Merryweather turns Maleficent’s squawking pet to stone.

There is a none-too-subtle implication that Merryweather is also one of the most competent of the fairies, as when Flora and Fauna attempt to sew and cook they fail miserably – but someone must have been completing these chores for the past 16 years. In case it wasn’t clear, Merryweather was my favourite of the three – spunky, a touch short-tempered, but caring, pragmatic and effective. Flora is bossy, while Fauna is just a bit goofy.

On top of the women, Prince Philip has a bit more personality about him than the other princes of the time – he actually got to speak and do some fighting, unlike Cinderella’s prince, who doesn’t even have a name. Philip sings, dances, and creates an attachment to the princess that is beyond just seeing her asleep (though yes, there is of course still an element of love at first sight). He fights and slays the dragon-Maleficent, though not without considerable help from the three fairies. His horse, Sampson, is a relatively obvious precursor to the very pet-like Maximus in the modern Tangled.

So why do I love the movie so much? One need only watch it to see the artistry, the stunning detail, that is a love letter (love drawing?) to the medieval aesthetic. The opening scenes are clearly high medieval, with the bejewelled book (opened against a background of the famous Lady and the Unicorn tapestry), scribe-like illuminated pages, feudal banners, knights, ladies in headdresses and more that evoke the Middle Ages.

There is little doubt in my mind that the artists had a strong affection for castles and studied many of them; Neuschwanstein may have been the inspiration for the gothic shape, but the interior courtyards and castle details could only have come from visiting medieval sites.

The stunning castle interiors are almost as evocative as the exteriors, with sweeping grand views of busy castle baileys, throne rooms, and decorated tower chambers that look not dissimilar to ones I have seen – granted without decorations – in castles recently. While I have never really tied my love of castles to this movie, it occurs to me belatedly that there must be some correlation.

I find myself frustrated when the classic Disney princess movies are compared to modern films like Frozen or Tangled, both excellent films but created in a different time period and with a different aim. The art and music is just as beautiful, but it is cannot be fairly compared to cels all drawn and filled in by hand. Newer films of course put more focus on equalising the position of the male and female lead, as well they should, but there is value in the older films. The value comes partly in Sleeping Beauty’s position as a work of art but also, like all art, as a mirror of the time in which it was created. Newer films make us appreciate how far we have come in character development – both male and female – and in what we expect from a story. Fairy tales are classic for a reason, and every generation re-writes them to best fit what they want the message to be.

For me, and for my best friend, we found the film an inspiration to be independent strong women like Maleficent or Merryweather. It certainly inspired me in my love for the Middle Ages and particularly castles.

But in closing, the most important question really must be: blue or pink?

One response to “My thoughts on – Disney’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’”

Fascinating analysis of Sleeping Beauty. Gave me a new perspective on the story/film and on some of the other classics!! Thank you!! Pam Moriarty

LikeLiked by 1 person