One of the most significant royal marriages of the Middle Ages took place at Poitiers, in May 1152. We know this because the chronicler Robert of Torigni – sometimes known as Robert de Monte due to his position as abbot of Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy – tells us in his Chronicle that, ‘Henry Duke of Normandy, either suddenly or by premeditated council, married Eleanor, countess of Poitou, who had only recently been divorced from King Louis [of France].’

It is a relatively short passage and quite matter of fact, but we can be confident as to its veracity as Robert had a close personal connection to Henry’s family: his abbacy was within the duchy of Normandy, and he would be made godfather of Henry’s second daughter. For such a significant alliance, Torigni is quite tight-lipped, though he makes an allusion to one of the more controversial aspects of the match: the bride’s very recent separation from her first husband. If you continue to read Torigni’s account, you discover that her first husband, King Louis, was furious but could do very little about it – I’m getting ahead of myself.

Firstly, who were Henry and Eleanor?

Henry

Henry, duke of Normandy, was known by several other monikers including ‘Henry Fitz Empress’, ‘Henry Curtmantle’ and ‘Henry of Anjou’.

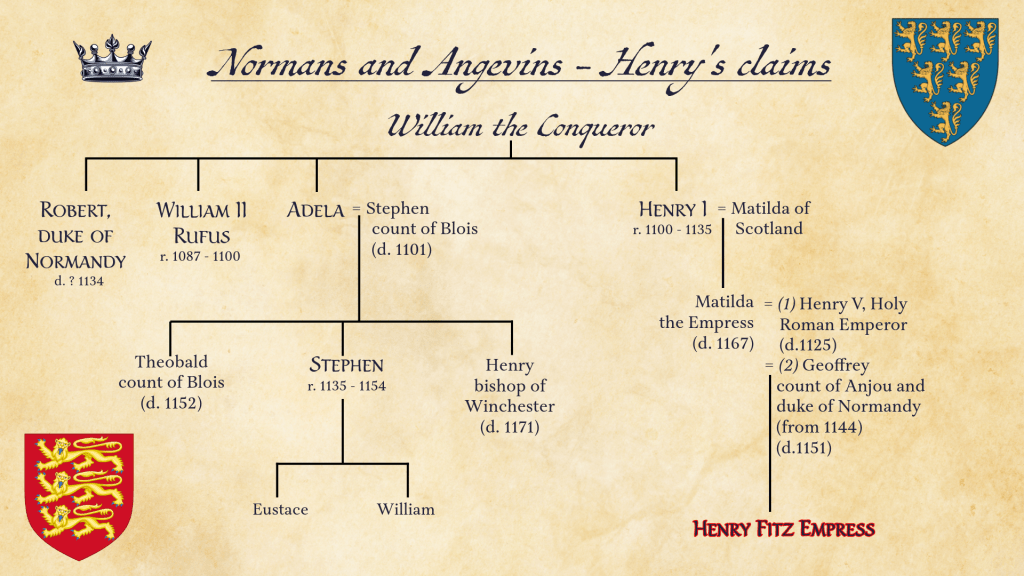

At the time of his marriage, he was 19 years old, and quickly becoming one of the most powerful men in Europe. His father, Geoffrey, had been regarded as one of the most handsome men in France, often called ‘Geoffrey le Bel’, and in his lifetime he was count of Anjou, Maine, and Touraine: a wealthy gathering of French lordships. Geoffrey was married in 1128 to Matilda, the only surviving legitimate heir of King Henry I of England. Though their marriage was notoriously unhappy – they in fact hated one another and separated at least once before being forced to reconcile – Geoffrey took up her cause when her throne was usurped by her cousin, Stephen of Blois.

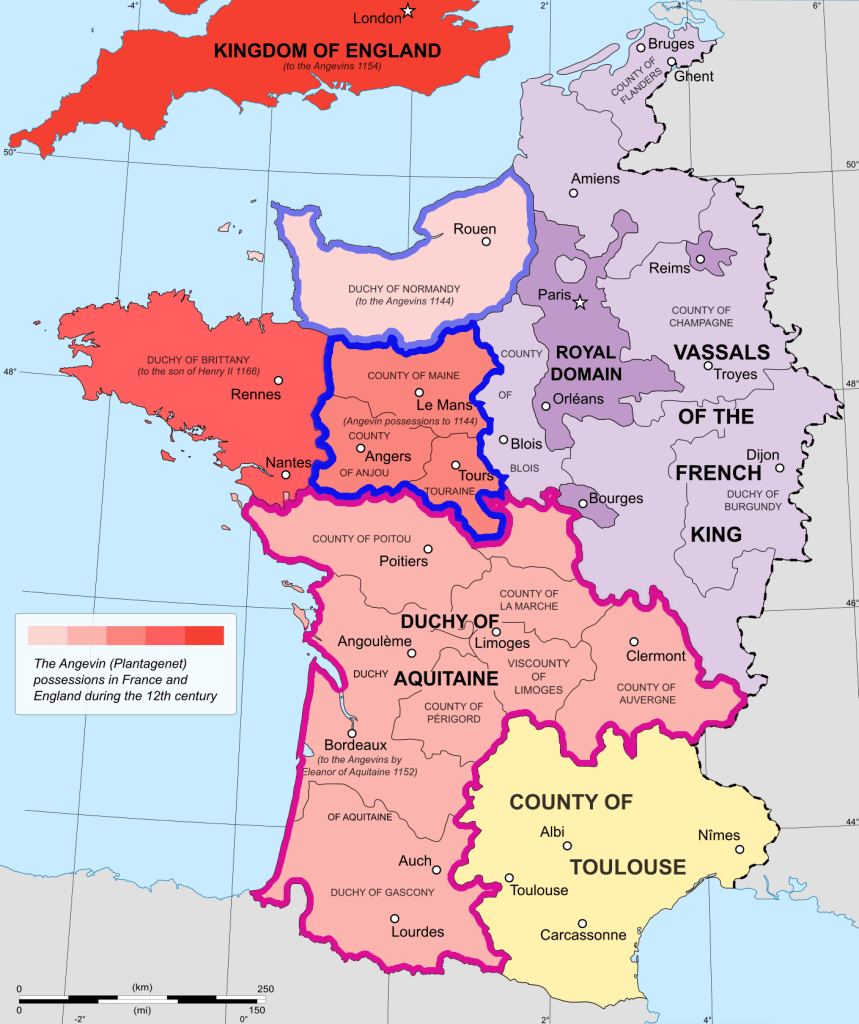

As part of that war, Geoffrey conquered Normandy and was granted the title of duke by the King of France. Normandy was one of the richest lordships in France, and this is how Henry, in 1152, was referred to as Duke of Normandy. His patrimony – the land he inherited from his father – was therefore immense, consisting of all the land outlined in dark and light blue, to the right. From his mother, he inherited a direct claim to the throne of England, and by the time of his marriage it was becoming increasingly likely that this claim would be fulfilled.

Eleanor

Eleanor was no less impressive than her new husband. She was heiress to the vast duchy of Aquitaine, outlined in pink above, and she had been Queen of France for fifteen years. During that time she bore two daughters and accompanied her husband on Crusade, stirring up gossip about her relationship with her uncle, Raymond of Antioch. She was referred to as one of the most beautiful women in Europe with enough regularity that it seems likely to have been true, and she was also educated and erudite, providing patronage to the arts through her court of love in Poitiers.

Her first husband, Louis VII, had loved her well but after fifteen years of marriage with only female heirs, he chose to set her aside on the grounds that they were too closely related under papal law. While seemingly absurd to modern eyes, this was a common ruse in the Middle Ages, when so many of the nobility and royalty were related within the prohibited degree set by the papacy.

The end of her marriage to Louis meant that she was suddenly ‘up for grabs’ in the European marriage market, and while Louis doubtless expected that he would be allowed to choose her second husband, there were more than a few lords who hoped to wed the richest heiress in France, with her permission or without.

A story is told that when Eleanor was travelling from Paris back to her capital after her divorce, she was forced to ride astride a horse to escape a bevy of men set on kidnapping and forcing her to marry. She managed to escape and reach the walls of Poitiers, where Henry would soon meet her.

The Marriage 💍👑

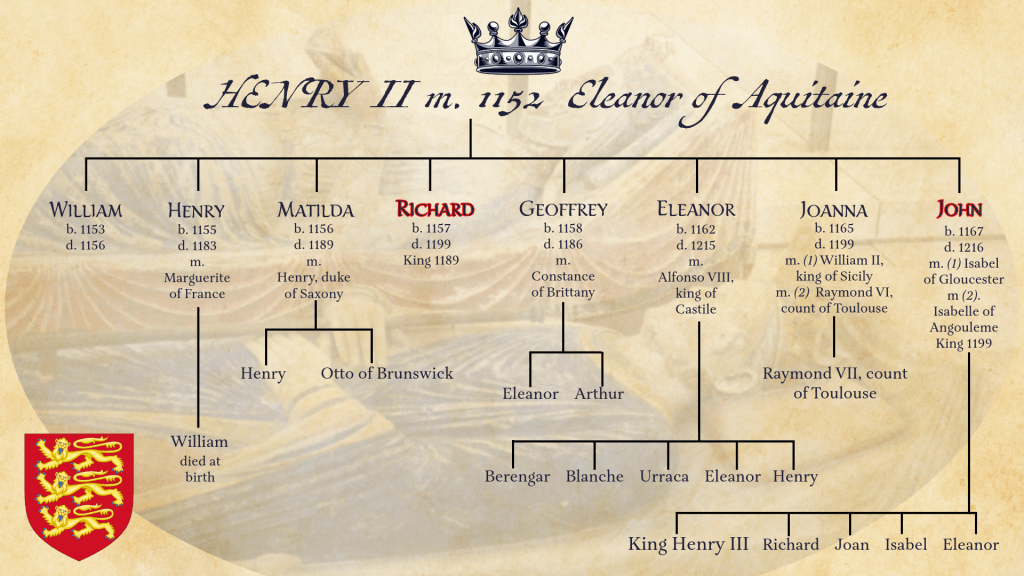

Even if one considers only the combination of lands, this was a significant alliance. In one day, Henry – by the right of his marriage – gained control of more of France than the king of France himself personally held. Quite a bit more, in fact – the royal domain is outlined in purple above. This infuriated King Louis on several counts: first, the obvious threat; second, the couple had not asked his permission to wed, which they were required to do as his vassals; third, Henry was as closely related to Eleanor as Louis had been; and finally somewhat related to the second point, Louis was now prevented from controlling Eleanor’s vast lands by marrying her to his own ally. Rubbing salt in the wound, Eleanor would go on to bear Henry five sons and three daughters – the first son just a year later.

At first, Louis attempted to exact punishment, but like most of Louis’ military endeavours it did not go very far, and Henry would spend most of the next thirty years outsmarting Louis both at war and at negotiation. This repeated humiliation was not a small part of the reason that Louis’ son, Philip, was so vehement in demanding respect from Henry and his heirs – he had no intention of repeating his father’s weakness, and he would gradually but progressively chip away at the English-controlled lands in France.

Within two years of the marriage, Henry was crowned King Henry II of England, forming an empire that reached from the border of Scotland all the way to the Mediterranean. The lands he inherited combined with those he gained through marriage to Eleanor made him the greatest landholder in Europe, even though a large portion was held as a vassal of the King of France. Henry therefore owed fealty to Louis for his French lands, a situation which would cause tension between two monarchs as to who would be superior. During Henry’s reign, his strength determined that he would be victorious; his heirs were less successful, while Louis’ were more so.

But that’s not all…

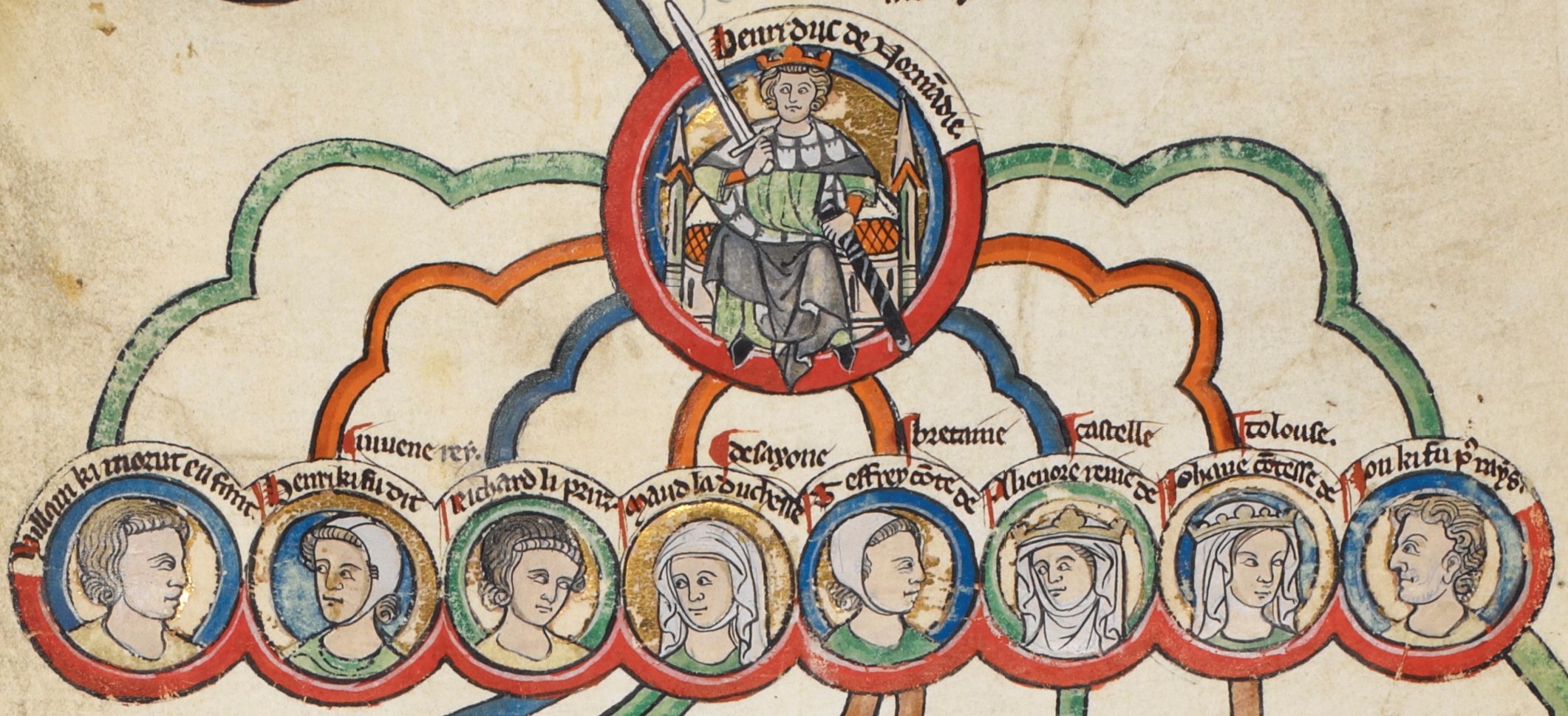

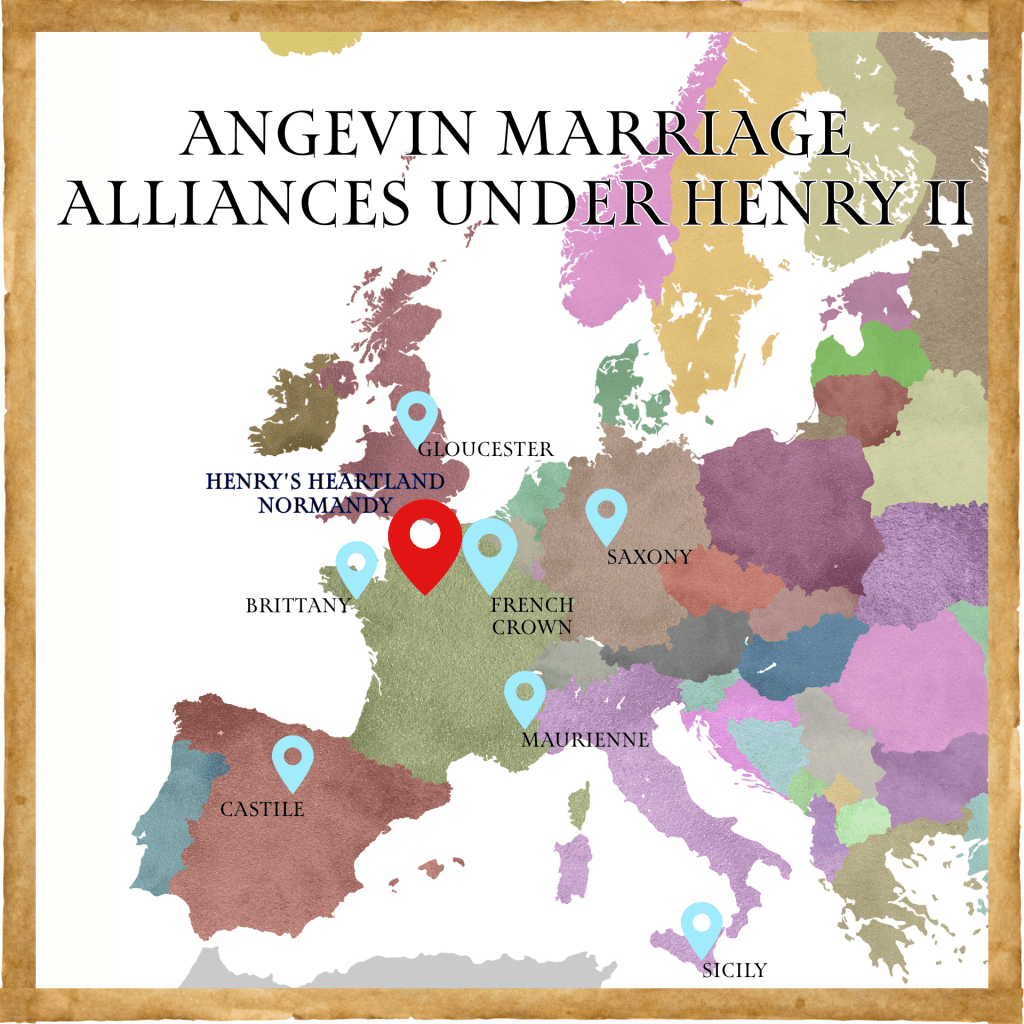

The marriage did more than just make Henry an incredibly powerful king. Due to his interests on the continent and his extensive holdings, Henry would make a series of marriage alliances with kings and lords throughout Europe, dictated by the borders of his new realm and by his many children.

Whereas in his grandfather’s day, the royal family of England tended to marry close by – French or Scottish royal, or even noble English spouses were common – under Henry, royal marital alliances included Castile, Sicily, the Holy Roman Empire and the royal house of France.

In the next generations these webs extended to Eastern Europe, the Byzantine Empire and re-secured alliances in France and the Spanish kingdoms The throne of England was now a prominent European player.

Through their children and grandchildren, Henry and Eleanor were progenitors of the royal houses of England, Scotland, France, Portugal, Aragon, Sicily and Castile, the Holy Roman Emperor, the counts of Toulouse and many more. The name by which Geoffrey le Bel was occasionally known, ‘Plantagenet’, would become the family name of the royal house of England for 400 years.

But it wasn’t all fun and games…

On the flip side, the crown of England would spend considerably more time and money on the continent than before; efforts to re-claim lost lands in Normandy and Aquitaine would drain coffers for generations, especially after Normandy was lost early in the thirteenth century. One might even argue that the marriage set the stage for the Hundred Years’ War of the fourteenth century; indeed France and England were at war as often as not in this period.

There is also the point to be made that Henry’s efforts to make a strong alliance for his last son, John, caused more dynastic damage than benefit. John, named ‘Lackland’ by his father, was almost ten years younger than his brothers, born when Eleanor was in her early 40s, and around the time Henry first met and fell in love with his famous mistress Rosamund Clifford. While Henry had arranged for each of his sons to have a generous parcel of land – his heir the Young King would inherit Normandy and the throne of England; Richard would inherit his mother’s lands of Aquitaine; Geoffrey was wed to the heiress of Brittany – there was simply nothing left for John. Henry would spend a great deal of time and effort searching for a solution, and in doing so betrothed John to the daughter of the count of Maurienne, in south-east France. The count insisted that John be granted something from his father, and so Henry named three castles that in fact belonged to the Young King, his heir. The frustration of having his father give away three of his most lucrative and strategically important castles drove the Young King into further disgruntlement, and spurred his eventual rebellion.

Furthermore, despite the clear success of Henry and Eleanor in creating heirs, their marriage was not a happy one – at least, not for long. Their sons grew to adulthood under the strong ruling hand of their father, and they were increasingly impatient for some power and influence of their own. Richard, who was raised mainly in his mother’s lands of Poitou and Aquitaine, was the most independent while Henry’s direct heir, the Young King, was perhaps the least – or at least believed himself to be. Henry was a master at controlling and manipulating those about him, but his sons proved to be his biggest challenge.

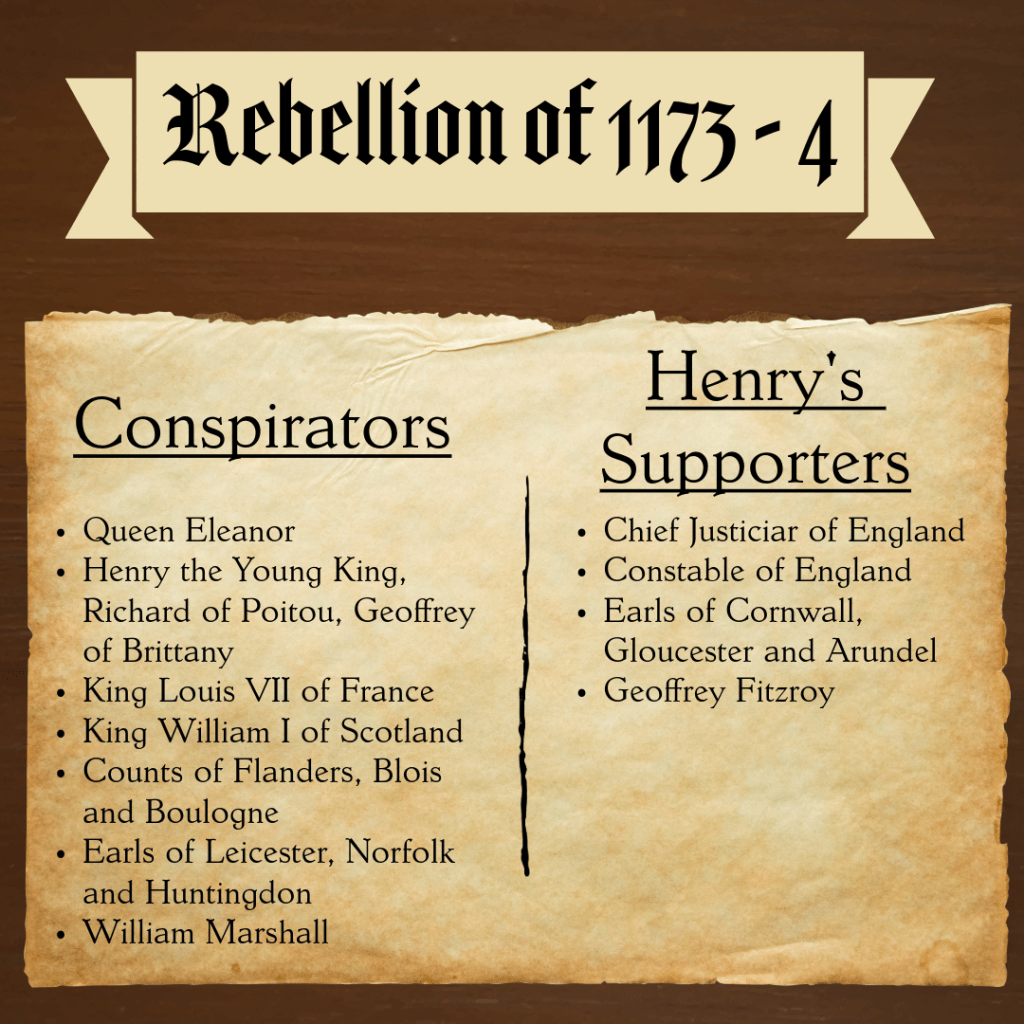

In 1173, goaded by Henry’s granting of castles to John and by the King of France, Henry’s sons agreed to a rebellion against him. They were to be supported by the King of Scots and a good potion of the French and English nobility.

Also in on the plot was Queen Eleanor, who by the early 1170s had been increasingly frustrated by her husband’s lack of action in Toulouse and too much time with his mistresses. (Eleanor claimed a right to the county of Toulouse through her grandmother, and both of her husbands had endeavoured to enforce that right, unsuccessfully. The Dukes of Aquitaine and Counts of Toulouse had been at odds for generations, and it was only with Eleanor’s daughter Joanna’s marriage to Count Raymond VI in 1196 that peace was established.)

The fact that Eleanor’s betrayal was one of the most painful to Henry was evident in the fact that after the defeat of the rebellion, he cast her into prison for 18 years, while his sons, he forgave. Side note, this story is one of my favourites about Henry – his entire family, the kings of France and Scotland, and half of his nobles all rebelled against him, but so ineffectively that he remained on the throne for another 15 years.

Henry and Eleanor were both unique in their time, as well as in history – powerful, charismatic, energetic and intelligent, they were both the perfect partners for one another and the perfect enemies. Though Henry’s Angevin Empire, with its heartland in Anjou and Normandy, would not survive long after his death, the significance of the English royal foothold in France beyond Normandy would echo for centuries, even if its extent was never what it reached under Henry and Eleanor.

One response to “This day in history – 18 May 1152”

Fascinating fill in to “The Lion in Winter”!!!

LikeLike