I have been thinking for some time that it would be nice to share here some of the research I have done over my years as a medievalist. While I have not formally studied for some time, I am always fascinated by how new views can be found on events that took place hundreds of years ago. So in this post, I will share with you a version of a piece of work which I put together for the International Medieval Congress in 2019.

I’ve tried to make it accessible, and I hope you will find it as interesting a topic as I did. It touches on some of my favourite characters in history, and the subject upon which I focussed for so long: medieval marriage.

But really, it’s a story – a story of the people involved in the negotiations, of their personalities, their strengths and weaknesses, and their priorities.

The title of the paper was, ‘An Unexpected Proposal: the suggestion of a marriage between Joanna of Sicily and al-Adil during the Third Crusade’.

Setting the scene…

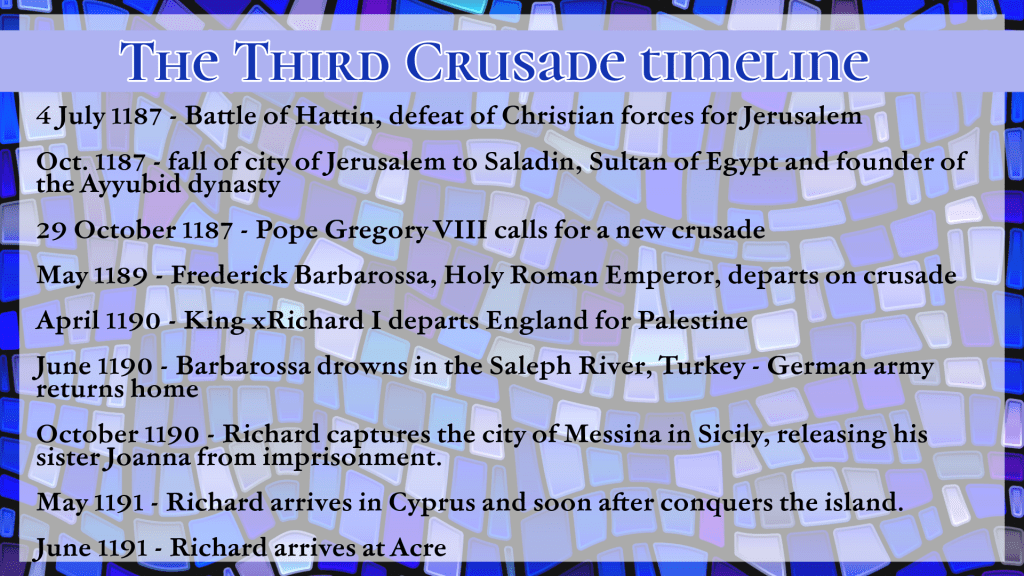

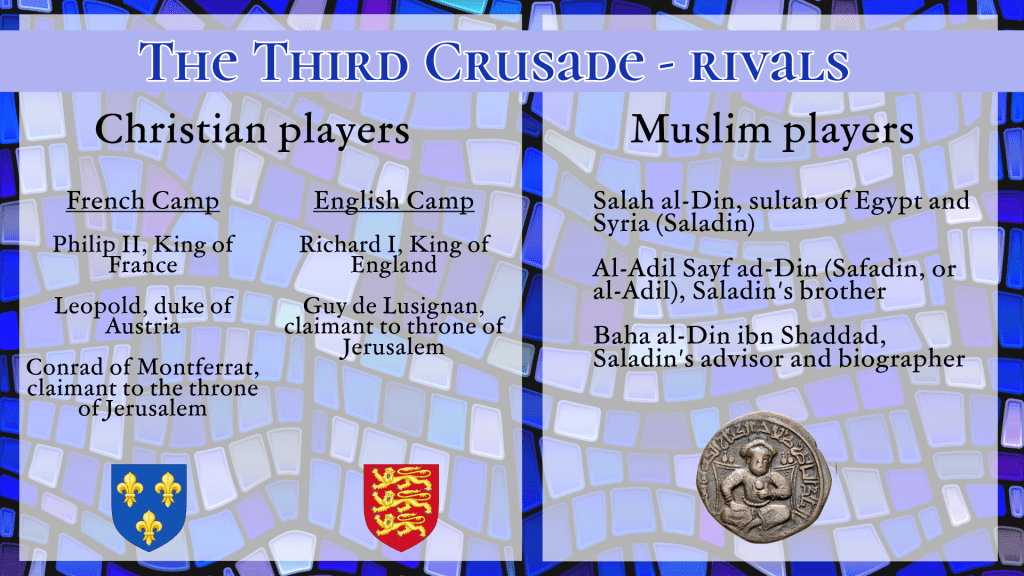

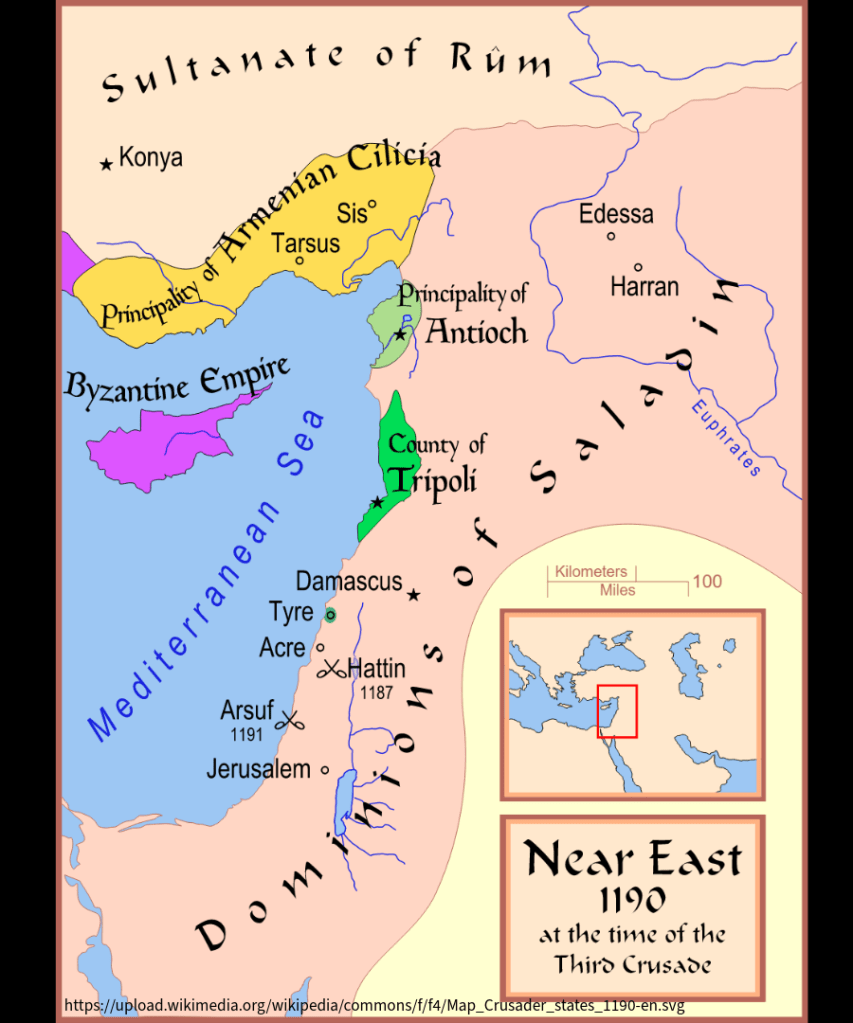

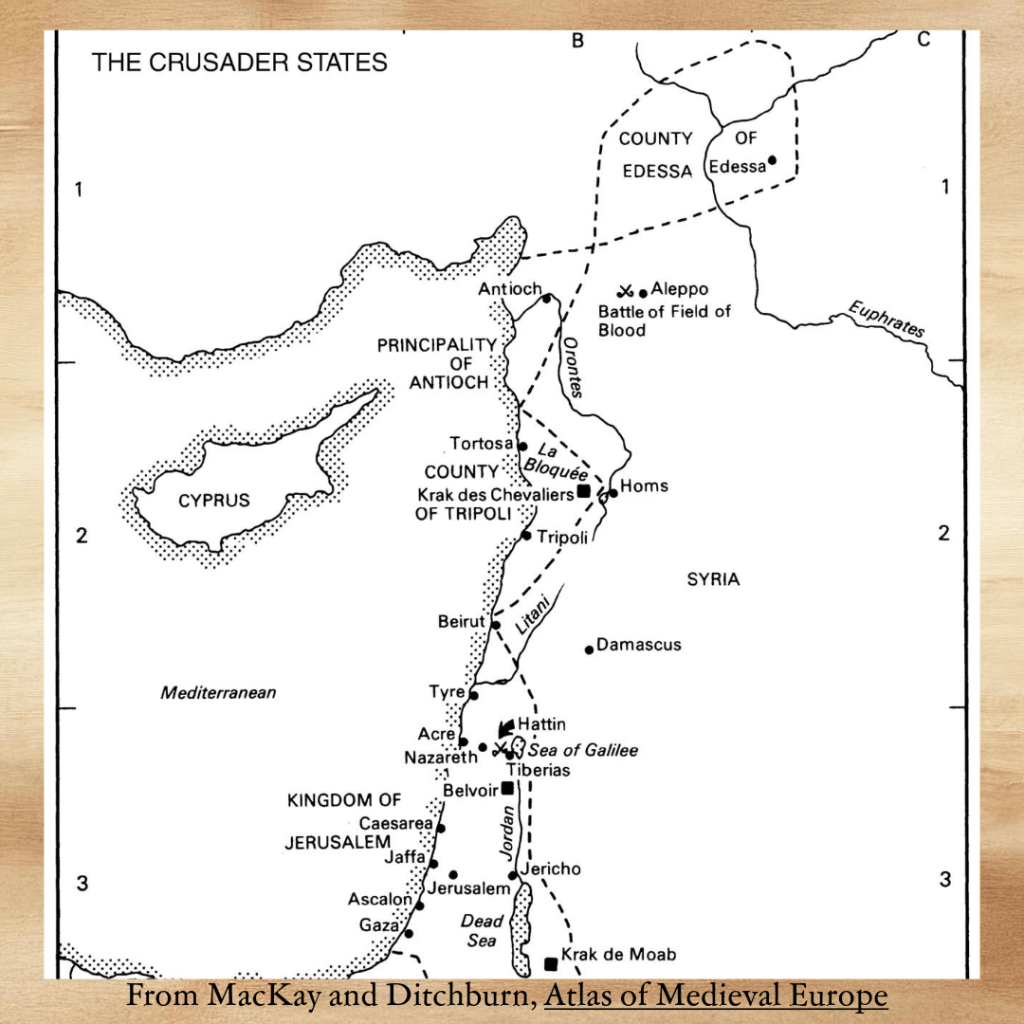

The tale begins in the midst of the Third Crusade, which was called in 1187 by Pope Gregory VIII after the fall of Jerusalem to the Muslim forces led by Salah al-Din, the sultan of Egypt (for the purposes of this paper, I will refer to him as Saladin, as do most western historians). Jerusalem had been captured by the Christian armies of the First Crusade in 1099, establishing the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem, so the loss of the city less than a century later caused most of the leaders of Europe to take notice. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa was the first to set off, but he drowned while crossing a river in Turkey, and his troops disbanded. This left the kings of England and France to lead the second wave of the crusade, and both Richard I of England and Philip II of France departed Europe in 1190.

Arrival in the Holy Land

In June 1191, Richard I, king of England – known in later years as the Lionheart – arrived in the Holy Land after a number of delays, to take his role as leader of the Third Crusade. He had left England some months previously but was held up first in Sicily – where his sister Joanna was the dowager queen – and then in Cyprus – where he was ‘forced’ to intervene when the Byzantine ruler, Isaac Komnenos, seized his supplies and belongings after a shipwreck. (it’s an interesting story, but not the point of this paper…)

There were plenty of other high-level nobles and kings present upon his arrival, including his now arch-enemy King Philip II of France, (they had fallen out in Sicily) and two candidates for the throne of Jerusalem: Guy de Lusignan and Conrad of Montferrat. But, almost from his arrival to dramatically lift the siege of Acre, Richard’s secured his position as the foremost warrior and hero.

The Itinerarium Peregrinorum (long title Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi), a Latin prose account of the Third Crusade that is likely to have been written from first-hand experience, tells us:

Even the enemy had a view on his arrival with one chronicler stating,

“He was wise and experienced in warfare, and his coming had a dread and frightening effect on the hearts of the Muslims.”1

Richard’s first few months were very successful; Acre, the maritime foothold of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, was captured, though the surrender was marred by the controversial decision to execute the Muslim garrison, probably more than 2,600 men. The motives for this action have been debated at great length, and you can read more in Gillingham and Spencer.2

However, the incident does give us insight as to Richard’s negotiating strategy. The treaty he had made with the enemy forces upon the fall of Acre were for Saladin to hand over a fragment of the True Cross and to release 1,500 Christian prisoners in exchange for the lives of the garrison and their families.3 When the terms were not upheld by Saladin, Richard followed through on his threat, without compunction.

Negotiations

The military aspects of the crusade have been the stuff of numerous articles and discussion, and the diplomatic negotiations were also an integral part of the relationship between the Christian and Muslim armies, as well as between Richard and Saladin. These negotiations have been examined thoroughly by Thomas Asbridge,4 but this paper looks in more depth at one particular part of these negotiations: a series of exchanges that took place in Autumn 1192, during which Richard suggested that the battle for Jerusalem could be ended by a marriage between his sister Joanna, the widowed queen of Sicily, and Saladin’s brother, al-Adil, often called Saphadin by European sources of the time.

Curiously, eastern sources discuss this proposal in some depth and are our primary evidence for it, while western sources are completely silent. This silence has always intrigued me. Many historians have focussed on the likelihood that the whole thing was just a joke, if it took place at all, but I believe it to be quite clear from reliable sources close to Saladin that the proposal was indeed made and considered in seriousness, at least at first.

Here I will make an effort to come to terms with why western sources leave the incident out, and I hope to answer some of the questions surrounding the event, which has been called ‘implausible’5, ‘extraordinary’,6 ‘remarkable’7 and ‘curious’.8

The proposal was not the first step in this round of negotiations. Rather, Richard had requested personal meetings with Saladin from the time of his arrival at Acre, but Saladin always refused.

For that reason, Saladin’s trusted general and brother, al-Adil, was his stand-in, and he met Richard in person on several occasions. They developed a rapport and traded regularly both food and gifts, and shared many meals.

In autumn 1192, Richard’s first offer, an opening gambit if you will, was one Saladin could never possibly accept. Baha al-Din, one of Saladin’s most trusted personal secretaries – and the writer from whom we get the most detailed account of these events – recorded Richard’s letter.

Saladin’s response, unsurprisingly, was a much wordier version of ‘no’.

He also reminded Richard that Jerusalem was as holy for Muslims as it was for Christians, and that the land had of course been theirs originally, before the First Crusade of the 1090s.

There was another player in these negotiations who was influencing Richard’s position. This was Conrad of Montferrat, one of two rivals to the crown of Jerusalem. Conrad was attempting to make his own agreement with Saladin, wherein the Muslim leader would confirm his possession of lands in Sidon and Tyre in exchange for Conrad’s attack on Acre, now garrisoned by Richard’s men.

Fortunately for Richard, the majority of Saladin’s advisors favoured a deal with the English king over one with Conrad. So, with his opening offer refused, Richard moved on to the second. There are three accounts of this incident, and I will look at each in turn.

Three Accounts

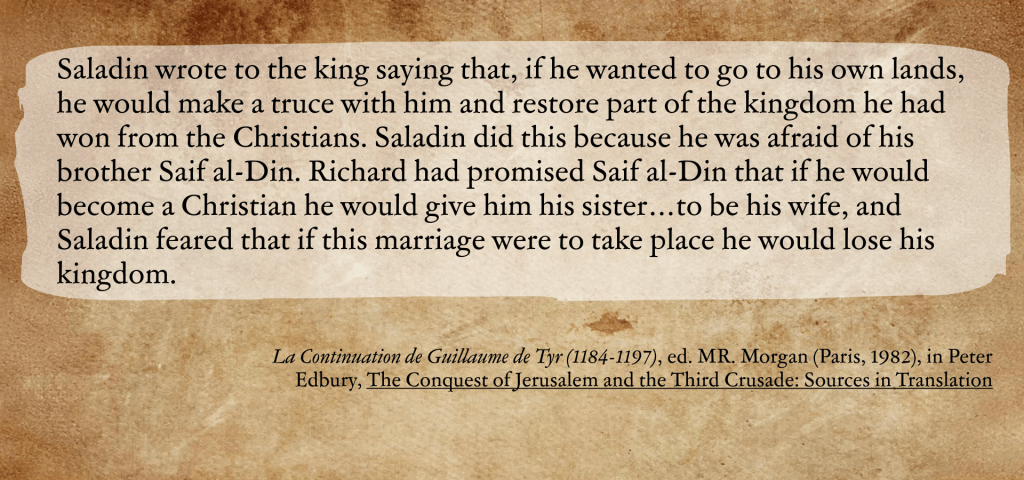

1. Old French Continuation of William of Tyre

This is the only surviving Christian source to mention the incident, and the source is often hostile to Richard. The writer states that Saladin was the initiator – the only source to suggest this, almost certainly in error. Further, the passage supports the belief held by some historians that Saladin was afraid of his brother. Certainly strife between two brothers is a common trope, but there is no real evidence of it, rather the sultan appears to have trusted and depended upon his brother. The overall accuracy of this version is therefore questionable.

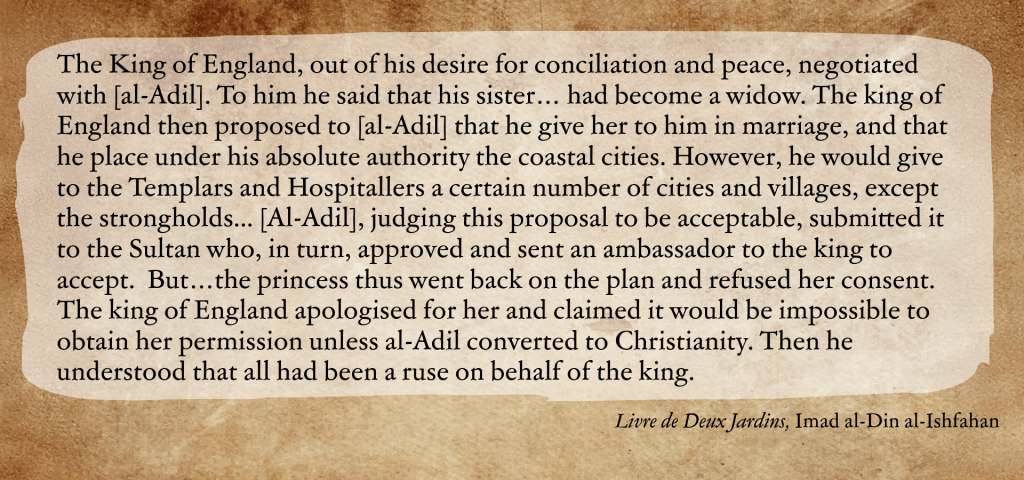

2. Les Livres de Deux Jardins, an account heavily based upon the writings of Imad al-Din al-Ishfahan, a Persian scholar who worked as a secretary to Saladin and was personally involved in many of the political machinations at court.

Clearly, this account is far more in-depth and indicates the more likely scenario that Richard initiated the proposal, directly to al-Adil, who passed the terms to Saladin. It was not a secret.

Furthermore, this account brings in a fact left out by the Continuation, that it was Joanna herself who was the spanner in the works, refusing to marry a man not of her religion. I’ll come back to this.

3. Baha al-Din, The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin. As mentioned, Baha al-Din was one of Saladin’s personal secretaries and a writer who is considered one of the most reliable for this period due to his first-hand knowledge of Saladin’s inner circle. His account is most comprehensive, covering Richard’s opening gambit, Saladin’s subsequent refusal, and Richard’s regroup to approach a second time. The delicate nature of the terms is made clear in that al-Adil required both Saladin’s trusted emissary, Baha al-Din himself, and a number of emirs to be present when they were announced.

Al-Din asserts that he himself was given the task of bringing the message to Saladin and bore witness to the reply. There were to be no secret negotiations between Richard and al-Adil, rather al-Adil was cautious, acting in self-preservation – Saladin may have not reacted well to hearing about the offer second-hand.

Echoing Imad al-Din’s account but with more detail, the story goes on. Saladin immediately approved the terms, ‘believing that the king of England would not agree to them at all and that it was intended to mock and deceive.’9

Baha al-Din also confirms Joanna’s involvement, stating that she was very displeased, ‘How could she possibly allow a Muslim to have carnal knowledge of her!’ instead asking al-Adil to convert. (remember of course that she was Catholic and this was the Middle Ages – it was entirely unheard of to marry a non-Christian). With regard to this refusal of Joanna’s, I do have my doubts about whether Richard would have allowed the prospect of peace in the Middle East to be ruined by his sister’s temper tantrum. The fact that the story is repeated by both Muslim writers makes it more likely that Richard used her as an excuse to get out of a proposal with which he never intended to follow through.

What does it all mean?

What the sources indicate, then, is a diplomatic suggestion that, joke or not, was also quite daring. Al-Adil considered it so noteworthy that, rather than continue his personal tête-à-tête with Richard, he wrote immediately to his brother. If the brothers were aware, as Baha al-Din relates, that the proposal was a joke, they certainly reacted in a serious fashion. They may also have wished to call Richard’s bluff.

So one has to ask of Richard – why? Was the proposal merely a distraction? Did he do it just to see what Saladin and al-Adil would do? It could have been a test of al-Adil, a way of assessing his loyalty to his brother – certainly Richard himself had no reason to believe in brotherly bonds and knew how precarious the relationship could be, so perhaps he hoped that al-Adil would leap on the suggestion to gain power over his brother.

Or perhaps he hoped that Saladin would grow to view his brother as a threat. Either way, Richard would be causing dissension in the ranks, which could only be to his advantage.

One can understand the Muslim writers’ assertions that Richard never intended for the proposal to be taken seriously when one looks at the rest of the tale. When Saladin accepted the offer, Richard was forced to scramble for a reason why Joanna could not, in fact, be married: he would have to ask the pope (dowager queens in Europe could not remarry without his permission), and that could take months. Richard suggested the al-Adil could have his niece instead, of course she was in Europe so again another delay…this is not the sign of a well-constructed plan. Richard may even have fibbed, saying that his Christian colleagues objected to the idea – but if the Christians had been asked, surely one chronicle somewhere would have mentioned it?

Finally, if this was a real proposal, part of a long-term strategy to end the warfare and allow Richard to return to Europe where the king of France was chipping away at his empire with the help of his brother John, why is it not in the Itinerarium Peregrinorum?

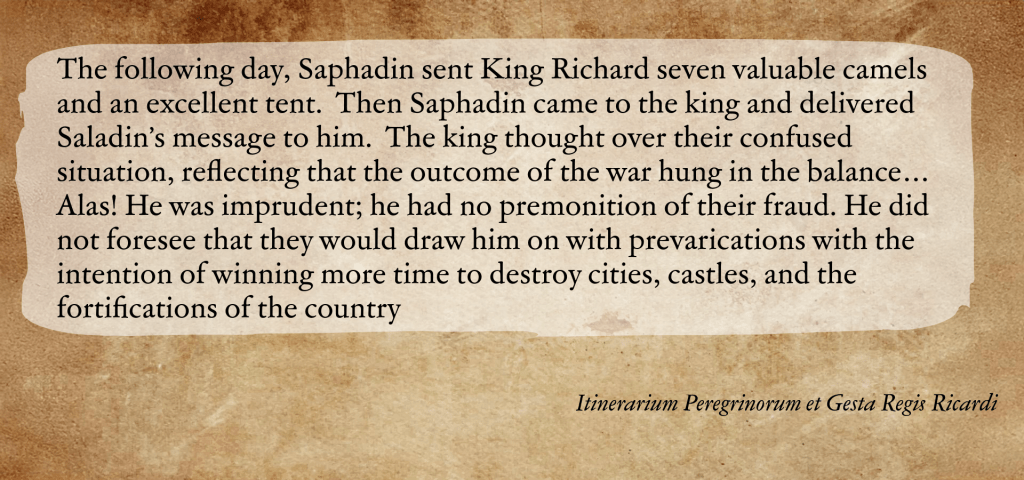

Because this period of negotiation IS there:

I feel this section to be a bit harsh on Richard. He was more than experienced at the art of war and negotiation, and would never have allowed himself to be distracted. Rather he would have been perfectly aware that a period of negotiation did not mean cessation of hostilities – frequently the opposite. Instead this indicates that the writer, whoever he was, had no knowledge of the more delicate negotiations taking place in the background, or if he did, he left them out. Which was it?

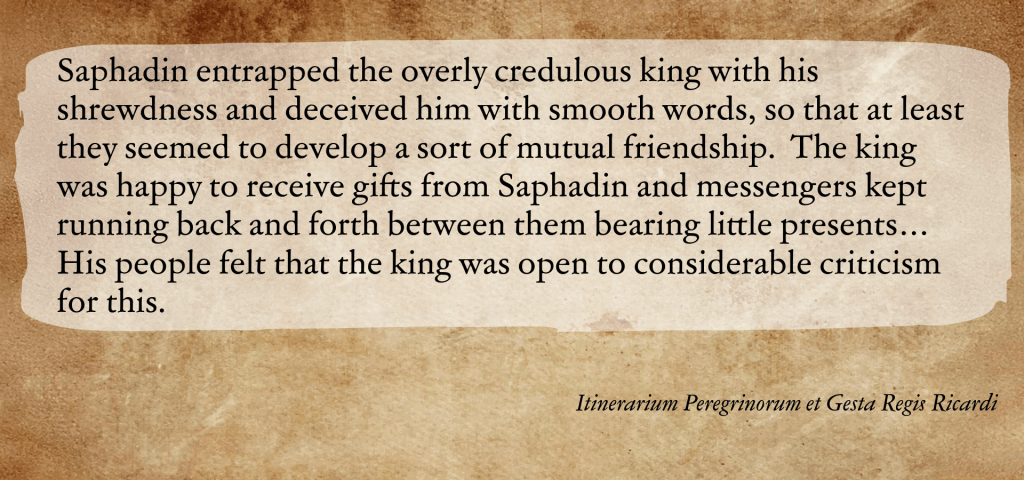

We cannot know for certain, but the only reasonable answer for either the writer leaving the story out or for Richard keeping the proposal a secret lies in Richard’s reputation. A little later, the writer of the Itinerarium alludes to the problem:

One has to remember that just because Richard was leading the crusaders did not mean that he was supported by all of them. In fact there were French factions – and others – who were seriously adverse to Richard’s strategies, particularly what they saw as his reticence to march directly upon Jerusalem- a true strategist, Richard was hoping to establish a solid base from which to attack the city, rather than attack directly.

A French source tells us that Richard had been overruled in his wish to approach Ascalon, a strategically vital city: whoever controlled Ascalon also controlled access to Egypt, Saladin’s home base. Its significance is evident in that Saladin himself had made it a priority to re-capture Ascalon in 1187 prior to his march on Jerusalem – this tactic was one Richard hoped to emulate, but could not convince the other Christians. They remained focused, inexorably, on relieving the Holy City.

Richard would have been considered even more suspect and likely found himself in danger had the majority of the crusading host discovered that he was offering his sister to a Muslim, rather than fight the infidels courageously for Jerusalem.

And it is here, I believe, that an answer may be found.

I have no doubt that Richard made the proposal, as suggested by two reliable Muslim sources, both very close to Saladin. It is possible that Richard’s closest advisors knew of the proposal and objected, but he mostly ignored them. However, the lack of inclusion in Christian sources such as the Itinerarium, which was unlikely to have been written by someone with the level of access to Richard that Baha al-Din had to Saladin, indicates a lack of widespread knowledge of the proposal. It is quite reasonable that there would have been a lot of detailed negotiation taking place which a member of the general crusading force would not know about, but which Saladin’s personal secretary would. An every-day crusader would also be more aware of the threats to Richard’s reputation that his close relationship with al-Adil caused.

The Muslim sources go into more depth about the gifts and offer a more detailed timeline than the Christian sources, and are generally better informed about the relationship between Richard and al-Adil. Richard was a bold strategist, and his life shows numerous examples of the willingness to make extreme choices in order to get what he wanted – he took part in several rebellions against his own father, beginning in his teenage years; he alienated the king of France by refusing to marry his sister and choosing another wife; he regularly led his armies into battle even when his life was in serious danger.

So, I do not see it as uncharacteristic for him to have made a proposal, almost off-the-cuff, just to see what kind of reaction he would get. But he would have been aware of the danger involved: his strategies were often questioned, he was frequently ill while in the East, and his kingdom was in serious peril during his absence. His reputation was not so strong that it could have suffered the kind of serious outrage which would have arisen had a French crusader heard of the proposal.

Muslim sources tell us what happened, but the details in the Christian sources actually hint more clearly at why the incident was omitted, or kept secret – it had to be.

As for the incident being implausible, I personally am not surprised by anything Richard did – he was bold, intelligent, witty, arrogant, and not above extreme negotiation. This time, he was up against an equally skilled strategist who called his bluff.

But Richard had some good luck. The proposal was refused by his own sister, and the counter-proposals that al-Adil convert or wed Richard’s niece, were passed over.

So, Richard never had to face a council of European and French nobles to explain that the Crusade was over because his sister was going to marry a Muslim prince. But it is intriguing to wonder what might have happened if he had…

- Baha al-Din, p. 150. ↩︎

- John Gillingham, Richard I, p. 169 and Stephen Spencer’s article. ↩︎

- Gillingham, p. 162. ↩︎

- Thomas Asbridge, ‘Talking to the enemy: the role and purpose of negotiations between Saladin and Richard the Lionheart during the Third Crusade,’ in Journal of Medieval History. ↩︎

- Gillingham, p. 184. ↩︎

- Malcolm Barber, The Crusader States, p. 350. ↩︎

- Charles J. Rosebault, Saladin: Prince of Chivalry, p. 277. ↩︎

- Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, p. 212. ↩︎

- Baha al-Din, p. 188. ↩︎