Carcassonne was the ultimate destination for the trip to France my mother and I made several years ago, during which we met in Toulouse and travelled on the train further south. I took so many pictures and was so in love with the city – both medieval and modern – that I have had to divide my posts into three, starting with the château, the glorious jewel in the crown of an already impressive restored medieval city.

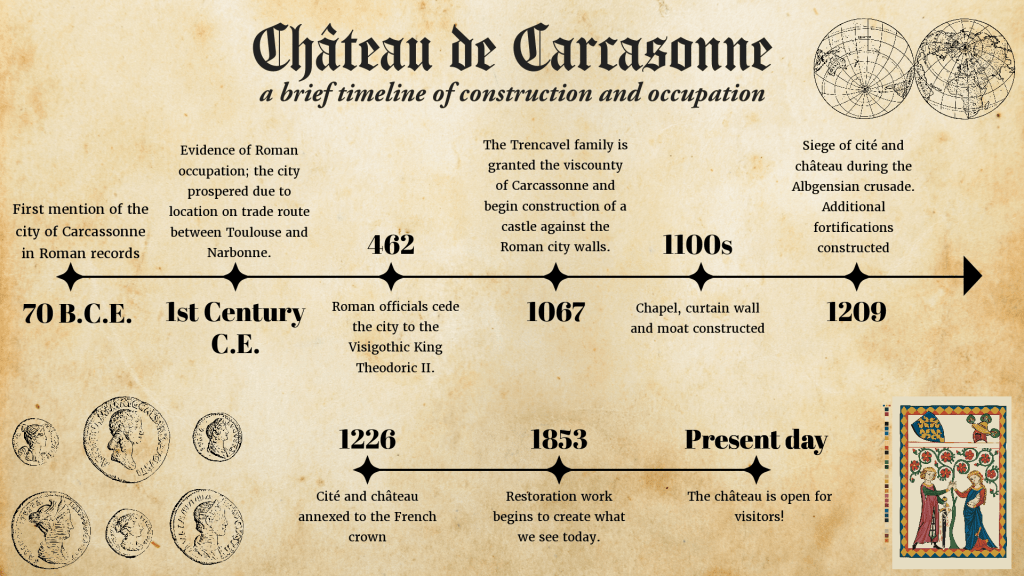

I’ll speak a bit here about the history of the château and how it was built and used, but here is a short timeline of the significant dates in its history:

In an experience a nearby Englishman declared ‘stereotypically French’, Mum and I hoped to visit the château on our first full day in the Carcassonne. However, upon arriving at the gates we discovered that it was closed due to strike action. So, we enjoyed a stroll around the cité instead, and later I took a long walk around the walls. We did enjoy a cup of coffee nearby, and I managed the first of many pictures of the exterior walls and moat.

The château’s history began in the 11th century, when the Trencavel family became viscounts of Carcassonne. Over the course of the next century, the family constructed a living space built against the Roman city walls, and continued to fortify as the years passed. There are patches in the walls today that are clearly Roman in origin, and it remains awe-inspiring to me that something erected almost 2000 years ago can continue to be structurally sound.

The north part of the inner rampart still has several 4th-century Roman towers. They are U-shape, and red brick is inlaid in the stone, in parallel lines and around the window arches. The bases of these towers are solid, making them very sturdy and explaining their longevity.

The defensive intent of the castle is more than evident as one enters across the moat – now a garden – and through the massive barbican.

The gatehouse exists separately from the rest of the castle, as is evident in the last photo above, in case it was taken – there is an open area, now where tourists gather, but once a space to muster troops in case of attack. The entrance has two portcullises – the gigantic heavy gates famous for closing at the wrong time, or just in time, in many movies – each operated from a different floor, so that no one soldier could cause danger through treachery. Needless to say, there are also projecting towers with arrow loops for bows, crossbows, and other projectiles – this was not an easy place to gain entrance by force.

Once through this dangerous, imposing block, one enters the courtyard, a wide open area with several trees. Around the edge of the courtyard are the remainder of the palace buildings as well as clear evidence of buildings now gone.

The keep part of the residence built in the 12th century reveals several phases of building, including outlines of crenellations that were constructed during the period of the Albigensian Crusades. These were filled in as the height of the keep was added to, and holes are visible in the stonework for wooden beams.

From the courtyard you can enter the keep and explore the ramparts, which have been reconstructed to appear more like they would have done when in use. Hoarding has been re-built – it is missing off most castles – and it gives you a real sense for what defenders would have experienced.

The hoarding is the wooden gallery installed on top of the ramparts as an additional defence during sieges. The beams supporting the hoarding slid into holes in the masonry, and openings in the floor allowed for arrows, stones and possibly hot oil to be dropped onto attackers below. The timber was covered in wet animal skins to protect it from fire arrows.

Inside the keep, a display has been made of masonry that has been rescued from various parts of the cité including the fountain, the knight effigy below, and much more.

Mum and I spent a good deal of time inside the keep, wandering through the rooms and for me, recalling bits of history I had known about the counts of Toulouse, the Trencavels, and the Cathars – all mostly firmly left in my undergraduate years of study.

The Trencavels were descended initially from the viscounts of Albi, a city about sixty miles or so north. They acquired Carcassonne through marriage, and by no means experienced an easy time of ruling the surrounding lands; there were revolts against them in the early twelfth century, and they were expelled from the city for four years between 1120 and 1124. They were also on occasion at odds with the counts of Toulouse, their powerful nearby neighbours.

The end of the family’s power came in the early thirteenth century when they, like the nearby counts, found themselves embroiled in the crusade against the Cathars directed by Pope Innocent III. Arguably one of the most powerful and influential of medieval popes, Innocent III was known as a reformer, and one of his targets was the centuries-old sect of Christian heretics who believed, amongst other things, that the pope and Catholic clergy were corrupt. To Innocent’s frustration, though, the Cathars were tolerated by the counts of Toulouse, and there were a number of powerful noblemen who embraced the faith. Count Raymond VI refused to assist the papal delegation of monks sent to stop the heresy, even after he was excommunicated in 1207.

To shorten a long story, in 1209 the pope declared a crusade against the Cathars – also known as Albigensians due to their association with the city of Albi – and the city of Carcassonne became a target due to its high population of Cathars. It was besieged and surrendered in August 1209, after which many other local towns followed suit. The viscounts clung tenuously to the city until 1226 when it was formally annexed to the French king, Louis VIII. After this point, a royal seneschal was the primary resident of the château, and many of the defences were reinforced to protect him from the often rebellions local population – southern France at this time was not known for its love and loyalty of the crown.

You can read a lot more about the history of the château online, and I found this guide in English to the cité itself.

As I have mentioned in a previous post, I am quite the curmudgeon when it comes to castles, and I vastly prefer the castles that were built for defensive rather that decorative purposes. Carcassonne is a fantastic mix of both – it has been restored to look almost fairytale-like, but maintains its authentic, defensive feel. The views from the walls show why it was such a significant fortress, and the layers of aging stone provide a history lesson in themselves.

Even on a rather overcast day, we had a wonderful visit and the clouds offered an air of mystery and drama that the bright sun the day before had not. There is no question that this is a spectacular location to visit, whether you are a historian, a fairy-tale lover, or just a tourist looking for a good way to spend the day. I am excited now, having re-visited my enormous cache of pictures from this trip, to spend a while sorting through and finding the best for you all. Suffice it to say, I would return to Carcassonne in a moment.

And to finish, one last view, which I think could have inspired Disney just as well as the fabled Château d’Ussé.