And so it begins.

I have endless, unrepentant, unflinching affection for Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Anyone who read last year’s post on Christmas movies will have a feel for this, but I wanted to dive deeper. I love the language, the story, and the memories that the tale evokes. It has been part of my Christmas tradition for as long as I can remember. We read the story, watched adaptations on TV, went to the play, and had a series of Christmas ornaments depicting the characters. I cannot imagine a time wherein I did not know the story, and was not able to quote at least the first two pages by heart. But I get ahead of myself.

Below, I’ll be looking at Dickens’ writing, the story itself, why I love it so much, and finally some of the film adaptations that I appreciate.

The writing

Dickens is considered a master for a reason – the richness of his prose draws one into the scene inexorably, painting a picture so clear that there is no question as to what he is envisioning. His descriptions of Victorian London are, like in many of his works, of a city that is grimy, cruel, icy cold and full of hard people living hard lives. The poverty is palpable, in both the streets and the small house of Bob Cratchit, often with an ugliness that is different from what we see today. But amongst that hardness is beauty – the goodness of Christmas, of people caring for one another and creating joy so that we cannot entirely sink into despair. Even when brutal, his writing is beautiful – his similes and metaphors unique, concise, and often humorous.

The ancient tower of a church, whose gruff old bell was always peeping slyly down at Scrooge out of a Gothic window in the wall, became invisible, and struck the hours and quarters in the clouds, with tremulous vibrations afterwards as if its teeth were chattering in its frozen head up there.

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol, Stave One.

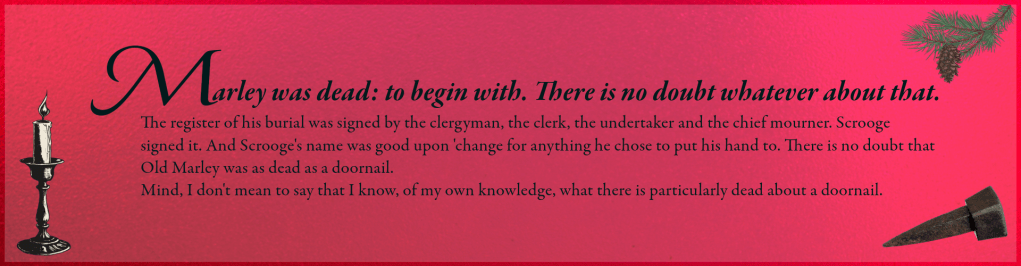

Perhaps most of all, I love his ability to forget the formality of writing and to speak to us as equals, as if we are in the room with him. He seeks confirmation from us as to the wisdom of a simile (what is there particularly dead about a doornail?), and ensures that we understand the significance of his choices. He wants us to know that he spent a great deal of time clarifying Marley’s deceased state because it is vital.

There is no doubt that Marley was dead. This must be distinctly understood or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate. If we were not perfectly convinced that Hamlet’s father died before the play began, there would be nothing more remarkable in his taking a stroll at night, in an easterly wind, upon his own ramparts than there would be in any other middle-aged gentleman rashly turning out after dark in a breezy spot – say St Paul’s churchyard for instance – literally to astonish his son’s weak mind.

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol, Stave One.

Every scene that we are taken to as the ghosts draw Scrooge through memories of his life is spectacularly vivid: an abandoned run-down school room, Bob Cratchit’s small house house, his nephew’s more opulent parlor, Fezziwig’s Christmas party – one of the scenes which every adaptation insists upon including, probably due to the sheer pervasive joy.

Dickens’ style of long, almost run-on sentences works particularly well in scenes like this, where the breathless nature of the structure helps to understand the breathless excitement of the story. Who would not want to attend a party like this one, lit by candles and firelight, full of dancing and punch and the most gracious host one can imagine?

Dickens chooses his words carefully, constructs them perfectly, with in depth descriptions that pull us into the world and make us feel that we are walking beside Scrooge on his journeys.

The story

It is not just the richness of the writing that I love – it is also the value of the story. It is more than just a wealthy, miserly man learning to give back; rather, it is also a tale of self-reflection. Few are as capable of harshly judging a person as that person himself or herself – throughout Stave (Chapter) One, it is evident that Scrooge knows perfectly well that people do not like him. He is happy with this, prefers it that way. It is only once he sees the impact he has had on others, the tragedies of his own life and the potential tragedies of those around him, that he can reflect back upon himself and realise he does not wish to be this way. He has made his own choices in life, he owns them, and decides to change his ways. It is a heroic and not easy thing to do. In his confrontation with the final spirit it is clear that just a desire to change may not be enough to save him, even has he beings to stammer his life-altering promise, that is also begging for another chance.

Now of course, Scrooge was faced early on with the threat of eternal damnation that Marley’s ghost revealed, but this was not enough to scare him. Not even when, in one of the more stark scenes of the story, he is forced to see other spirits desperately wishing that they could help a poor woman.

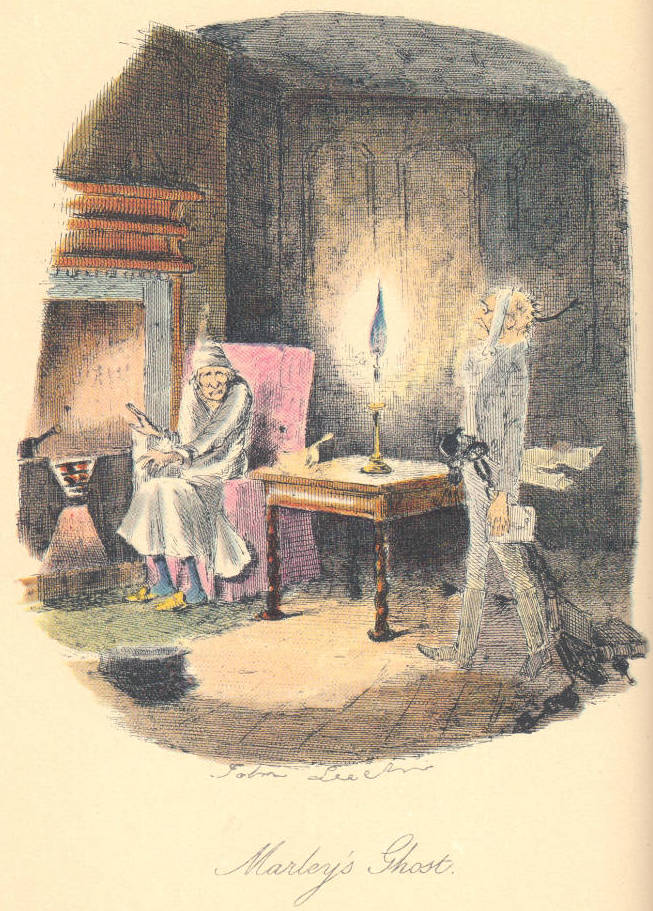

Below are two of the original illustrations that were published with the tale, by John Leech.

Instead, it is the terrifying figure of the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come, showing Scrooge how little the world will miss him, that really completes his repentance. He has been softened by the joy of the families he has seen, the love they show one another, by the Spirits of Christmas Past and Present. The horror of seeing his own grave is the ultimate in self-reflection. But I am not really here for an analysis of the story.

Why I love it

The quality of writing and the quality of the tale are only part of my affection for this story. It stems also, and perhaps primarily, from familiarity and memory. My father read the story to me, word for word, one stave each night, every Christmas for at least ten years. It is so ingrained in me that even when reading it silently (which I find hard to do), I can hear his voice and intonation, the way he would drop his voice half an octave when reading Scrooge’s dialogue and make the words more gravelly, or lighten the tone when reading Fred’s words (I suppose I should be relieved that he never attempted an accept). He read to me often when I was young, and would pause to explain words or phrases he thought I might not understand. In grade school, I surprised my class with my dramatic memorisation and performance of the first few pages of the tale for recitation day. I had always chosen a slightly different passage than my classmates – I preferred Lewis Carroll poems or Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses rather than something like the Gettysburg Address or Dr Seuss – and was generally shy. This piece of work which I knew so well and felt every word almost won me the class prize of reciting before the school, but not quite. I remember the moment well, decades later, and the confidence that the prose instilled in me.

Adaptations

I will fully admit that I have not watched every adaptation of A Christmas Carol, not in the least because there are just so many out there – more than 100 according to Wikipedia. Many older actors have attempted the role of Scrooge and can do the early staves well, the almost comic greed and cruelty. But the role also requires a softening, a growing humanity, which is both tragic and comic. And, I grow cross when there is no respect for the original prose – much of the dialogue can be pulled directly from the page, and I have always been a purist. I like when adaptations respect the source (perhaps I may write about my feelings on Jane Austen another time). And this source is sacrosanct.

There are two adaptations to which I return annually, as I wrote in last year’s post on Christmas movies.

The first is Mickey’s Christmas Carol. It is very short but contains all the original characters and despite the drastically fast visitation by the final spirit gives a good feel for the story. Plus, Scrooge McDuck is excellent. This is the first adaptation I ever watched, and Christmas just doesn’t feel right if I haven’t had a 20-minute window to see it. I have particular affection for the way the three Christmas spirits are portrayed, and for Donald Duck as Scrooge’s incorrigibly cheerful nephew.

The second is The Muppet Christmas Carol. The puppets work quite well somehow and the musical numbers are both hilarious and impossibly catchy. The highlight is of course Sir Michael Caine’s absolute straight-faced portrayal of Scrooge. He could have been in a film with only human actors and have played the role no differently – and so it works. He is delightful to the end, and there is careful attention to maintaining quite a bit of the original prose and dialogue.

Finally, this year I decided to widen my experience and so settled down to watch what is in fact yet another Disney production of the story – the 2009 Robert Zemeckis film ‘starring’ Jim Carrey as Scrooge and several of the spirits.

I was prepared to be annoyed and dislike it, as I tend to be less of a fan of Carrey’s more recent work (the Grinch for example). However, I was pleasantly surprised by several aspects of the film, not least how close it sticks to the book and its inclusion of several scenes that are frequently omitted, such as all the bells in the house ringing prior to Marley’s arrival, meeting Scrooge’s young sister, the gradual aging of the Ghost of Christmas Present, and the couple who owed Scrooge money but were relieved by his death.

The dialogue is generally a direct quote of the text, and it is clear that Zemeckis has true affection and respect for the story.

Likewise though, there were some parts that I did have some issue with. Firstly, I am not certain the director could make up his mind who the audience is – some scenes seemed aimed at children, but others were very adult (the twins Ignorance and Want, a concept probably beyond children and visuals quite frightening for youngsters). I found myself distracted by the animation, trying to see the original actors in the faces on screen, though the latter faded in time.

Overall I found a lack of subtlety, even in a book that does not particularly deal in subtlety. Dramatic scenes were overdone in a way that is typical of Disney shows for children – Marley was creepy, disgusting, and scary but not necessarily unsettling; the many ghosts of former misers were a bit over the top; on several occasions Scrooge is shooting through the sky, falling, or being dragged or chased through London, which seems to detract from the truth that this is all, really, in his head. The film rushed through the Fezziwig ball scene, but provided one of the most touching and accurate breakup with Belle scenes that I have watched.

Perhaps most annoyingly for me, I found the portrayal of the Ghost of Christmas present generally just…wrong. It may be that it was Carrey in yet another character – Gary Oldman, who played Cratchit, might have been a better choice – but I found his laugh to be more sinister than jolly, and I prefer the more forgetful, simple-minded versions of the Muppet and Mickey adaptations. The spirit’s death in particular was upsetting, as we watched him dissolve to a skeleton and then blow away – I am not sure what the point of this is, when in the book he just vanishes, leaving Scrooge alone in the darkness, with the final spirit approaching. That sudden, drastic change is jarring and unnerving it itself. Personally I would have been happy to cut that scene shorter and spend more time at the ball, though I realise it is less integral to the story.

I did find it intriguing that Zemeckis used the Mickey version’s idea of having Scrooge falling into a grave, where a fiery coffin waits for him, with his final speech proclaiming to keep Christmas in his heart stammered out as he clings to a root. This is certainly more dramatic, but I always miss the idea of Scrooge fighting with the spirit to have it, “dwindle down into a bedpost.”

Finally, I felt that overall, Scrooge’s giddiness upon awaking and his whole changed demeanour was well done. I was distracted by it being Jim Carrey, as he always has a touch of the Mask mania about him, but the book is followed more closely with Scrooge meeting Cratchit at the office the next day, which I enjoyed. This allowed Scrooge to go to his nephew’s house for dinner, and there is a moment of hesitation, of fear that he will not be accepted, and I think that is important to see.

Anyway. I have waffled on about this version at length partly because I had put off watching it for so long, and partly because it is so clear in my mind. I think, in fact, that it would be a very good option for children to watch to get a feel for the story (perhaps not too young though, as it is scary in places – I have a new appreciation of what is scary after terrifying my niece with Lady and the Tramp). I found the animation jarring but I understand that this style allowed Zemeckis to create the world with an authenticity that would otherwise be incredibly expensive. It is interesting to realise that all three versions were released by Disney, though in very different eras (1983, 1992, 2009) and with very different production teams. I look forward to, in time, exploring non-Disney adaptations. Above all, I really loved Gary Oldman’s Bob Cratchit, and the fact that he was able to narrate at the end, finishing of course with Tiny Tim’s observation, “God bless us, every one!”

Post script

It was suggested that I attempt to write about why A Christmas Carol is still relevant today though it was published nearly 200 years ago. I feel that Disney’s continued funding of new adaptations, and the continued popularity of plays and musicals of the story really make that suggestion moot. There is no need to analyse why it is still a popular story; it speaks for itself.